Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is William Goldman’s first original screenplay. A Western script written in the late-1960s, its style and format nevertheless has more in common with the continuities of the silent era than with other screenplays available from Goldman’s period. This may not be coincidence.

Goldman’s script fictionalizes the criminal careers of Robert Parker (a.k.a. Butch) and Harry Longabaugh (a.k.a. Sundance), focusing on the period between their infamous Union Pacific Heist in 1899 and their purported deaths in 1908, a period in history that also saw the birth of Western movies with Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery in 1903. The emergence of Western movies as popular entertainment is explicitly referenced in Goldman’s script, where he depicts Butch and Sundance watching a dramatization of their exploits shortly before they die. Even the opening titles of the motion picture starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford uses a silent film motif.

Goldman’s screenplay bears more than a passing resemblance to the continuity format perfected by Thomas Harper Ince in the mid-teens of the 20th Century. In his day, Ince was a famous writer, director, and producer of Westerns, and his surviving continuity for the one-reeler Satan McAllister’s Heir, co-written in 1914 with C. Gardner Sullivan, offers an interesting study for comparison. Ince, of course, was a contemporary of the real Butch Cassidy (though 16 years his junior) and wrote Satan only six years after Cassidy’s purported death. If Goldman wanted to write a Western set at the turn of the century, he’d have good reason to research the popular Westerns of the early silent era, including Ince’s work.

Compare the opening sequence from Satan with the first page of Butch.

First Satan:

1. CLOSE UP ON BAR IN WESTERN SALOON

A group of good Western types of the early period are drinking at the

bar and talking idly -- much good fellowship prevails and every man

feels at ease with his neighbor -- one of them glances off the picture

and the smile fades from his face to be replaced by a strained look of

worry -- the others notice the change and follow his gaze -- their

faces reflect his own emotions -- be sure to get over a sharp contrast

between the easy good nature that had prevailed and the unnatural,

strained silence that follows -- as they look, cut --

2. CLOSE UP ON SATAN AT HITCHING RAIL BEFORE WESTERN SALOON

TITLE: "SATAN" McALLISTER, THE RICHEST, MEANEST AND MOST HATED RANCHER

IN THE WYOMING VALLEY

Satan is tieing his horse to the rail -- he finishes and looks brazenly

about him -- Satan is all that his name implies -- he is a sinister

gun-fighter, a man-killer and despite the fact that he is without fear,

a bully of the worst type -- he delights in hurting and abusing people

and dogs, and the more forlorn appearing they are, the greater his

delight in tormenting them -- everybody is afraid of him and hates him

-- he knows this and revels in it -- he exits, looking for trouble at

every step --

3. CLOSE UP ON BAR: SAME AS 1.

Flash back to the men at the bar -- they show Satan is coming and wait

uneasily, none of them knowing but that he will be singled out for

Satan's abuse --

4. EXTERIOR SALOON: WESTERN

Satan comes on from the sideline with a sneer -- have a lonesome

looking dog sitting before the saloon door -- Satan boots him off the

picture and smiles cruelly as he hears the dog yelp -- he looks about

for something else to abuse but finding nothing, exits into the

saloon --

Now Butch:

Is it possible that Ince’s Western continuities directly influenced the style and format of Goldman’s first screenplay? Only Goldman can answer that question (and I wish I could ask him). Both scripts narrate the action in explicit shots and cuts, both make liberal use of literary comment, and both offer asides for the crew to aid in or explain the execution of what is written into a filmed performance.

While this shooting script, dated July 15, 1968, is marked as the “final draft,” it differs significantly from the published version found in Goldman’s various books. In fact, the primary difference between the published version and this dated shooting script is that the latter offers more continuity-esque explicit technical instruction.

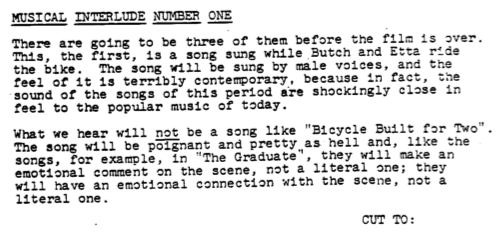

Take the following passage from the shooting script:

The first of these paragraphs is included in the published screenplay. The second is not. The reference to The Graduate, a recent hit film with a hit soundtrack, is particularly unusual in screenwriting. Numerous of these trims can be found between the two versions.

A significant change between the two is the closing image. In both versions, the narrative ends on a freeze frame of Butch and Sundance, but in the shooting script, the last image we see is Butch and Sundance lying on the ground. Whether Goldman revised this in a subsequent draft or director George Roy Hill simply improvised the famous closing image of Butch and Sundance bolting to their deaths, guns drawn, there is no question it offers the audience a more compelling final image. Indeed, that freeze frame shot was used in most of the film’s marketing materials.

If Butch’s style and format appears to be influenced by the silent continuities of Ince’s era, its tone is wholly Goldman’s own. Interestingly, it is this tone that Goldman has self-critiqued in his book, Adventures in the Screen Trade. “Some of it just makes me wince,” he writes, citing several passages of dialogue.1 I’m inclined to agree with Goldman about some of the “smartass” dialogue, and that the script, at moments, “suffers from a case of the cutes.”2 Those quibbles notwithstanding, Butch is one of the most quotable screenplays in the history of the form, while the personal touch Goldman gives his scene text narration and his penchant for hyperbole (“THE LONGEST TRAVELING SHOT IN THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD”) has influenced subsequent screenwriters such as Shane Black.

Black, who wrote Lethal Weapon, no doubt also drew character inspiration from Goldman’s successful handling of the buddy-film action/comedy genre combo. Goldman paints Butch and Sundance as a bromance for the ages, their deep affection and loyalty for one another buried beneath bravado and wit. While each can practically read the other’s mind in a dangerous moment, neither one knows the most basic facts about the other. Who needs biography when you’ve shared spilt blood? Even in their dying moments, they cling to one another with their jokes.

At its worst, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid helped to liberate late-60s screenwriting from the monotonous voice of the objective narrator, even if it occasionally went too far. At its best, it turned the Western genre on its head and defined male relationships in the cinema for a generation.