Originally the screenplay was called a scenario, or continuity script, and consisted of a list of scenes that described the silent action and camera angles. These first screenplays evolved from the economic necessity to pre-plan rather than rely on costly extemporaneous scene development on the set. Later, when sound on film was invented, words, sound effects and music were added [. . .] During the years of the studio system [. . .] screenplays included very explicit production instructions and were often rubber-stamped, ‘Shoot as written.'” — Margaret Mehring1

1.1.1. Overview.

If only the history of the screenplay were as easy as Mehring claims!

In his Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice, Steven Maras dispels several of the popular myths perpetrated in the above quote, for instance, (1) the myth of a direct evolutionary relationship between the screenplay, the continuity, and the scenario and the interchangeability of those descriptors, (2) the myth that the terms scenario and continuity were themselves easily defined in the era in which they were used, and lastly, (3) the sensational myth of the “Shoot as written” rubber stamp.2 Mehring even gets it wrong when she suggests that spoken words appear in the text only after the introduction of synchronized sound into film production, contradicting Janet Staiger’s testimony that the early scenarios contained “a scene-by-scene account of the action including intertitles and inserts.”3 Kevin Alexander Boon concurs with Staiger, when he writes that “dialogue was present in the continuity prior to sound, in the form of titles.”4

We cannot scold Mehring too harshly for her errors. The history of the screenplay is notoriously difficult to trace, due both to a problem of language (the word “screenplay” itself does not come into common usage until the 1940s) and to the fact that its earliest antecedents are private industrial documents, many of which have been lost to time. We will not attempt a comprehensive history of scripting — the process of writing for the screen — on this page. We mean only to outline a brief survey of that process’s development into the stable form recognizable to us today as the screenplay.

Page Topics:

- 1.1.1. Overview.

- 1.1.2. Antecedents

- 1.1.3. Alternative Forms

- 1.1.4. Sound and the Script

- 1.1.5. Standardization

- 1.1.6. Terminology

- 1.1.7. Discussion Topics

- 1.1.8. Footnotes

1.1.2. Antecedents. [Back to Page Topics]

If we cannot trace a direct lineage for the screenplay, we can survey a history of scripting practices. Motion pictures began as novelty, not narrative, but even some of the earliest filmmakers found scripting practices useful in the conception of their products. These early “scripts” were little more than brief synopses. “From 1896 to 1901,” writes Isabelle Raynauld, “scenarios were written in synopsis form and rarely were longer than one paragraph. Many, in fact, were even shorter: they included a title and a one-line description of the action to be seen.”5 She goes on to note how these early protoscripts also served a marketing function:

For example, it was a common practice to print the screenplays in full (long mistakenly considered to be merely summaries) in company catalogues. In fact, early scripts were not only used as publicity material but also helped exhibitors explain the story to new, inexperienced spectators. For the first ten years or so, exhibitors would often hire a lecturer or bonimenteur to comment on and clarify the story during the projection of the film.”5

Excerpts from the Edison Studios catalog offer examples of such synopses, such as 1897’s “Pillow Fight” (“Four young ladies, in their nightgowns, are having a romp. One of the pillows gets torn, and the feathers fly all over the room.”)7 and the decidedly more racist “A Morning Bath” (“Mammy is washing her little pickaninny. She thrusts him, kicking and struggling, into a tub full of foaming suds.”)8, the original text of which is censored in the Library of Congress’s online archive.9

After 1901, as films grew in length and narrative concerns grew more prominent, the importance of scripting as a conceptual tool increased. Out of this need for narrative coherence, the scenario proper was born. “The film script was born,” observes Béla Balázs, “when the film had already developed into an independent new art and it was no longer possible to improvise its new subtle visual effects in front of the camera; these had to be planned carefully in advance.”10

In his Script Culture and the American Screenplay, Kevin Alexander Boon draws from several early scenario examples, including Georges Melies’s A Trip to the Moon and Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery, to demonstrate the rapid development of scripting practices at the turn of the century. “Early predecessors of the screenplay did little more than frame the narrative context for a scene,” writes Boon. “One of the first major infusions of story into filmmaking was Georges Melies’s A Trip to the Moon (Le voyage dans la lune, 1902), which [. . .] involved a great deal of preparation from Melies. One part of this preparation was the writing of a sparse scenario [. . .]”11 The complete text of the Melies scenario follows:12

- The Scientific Congress at the Astronomic Club.

- Planning the Trip. Appointing the Explorers and Servants. Farewell.

- The Workshops. Constructing the Projectile.

- The Foundries. The Chimney-stack. The Casting of the Monster Gun/Cannon.

- The Astronomers-Scientists Enter the Shell.

- Loading the Gun.

- The Monster Gun. March Past the Gunners. Fire!!! Saluting the Flag.

- The Flight Through Space. Approaching the Moon.

- Landing Right in the Moon’s Eye!!!

- Flight of the Rocket Shell into the Moon. Appearance of the Earth From the Moon.

- The Plain of Craters. Volcanic Eruption.

- The Dream of ‘Stars’ (the Bolies, the Great Bear, Phoebus, the Twin Stars, Saturn).

- The Snowstorm.

- 40 Degrees Below Zero. Descent Into a Lunar Crater.

- In the Interior of the Moon. The Giant Mushroom Grotto.

- Encounter and Fight with the Selenites.

- Taken Prisoners!!

- The Kingdom of the Moon. The Selenite Army.

- The Flight or Escape.

- Wild Pursuit.

- The Astronomers Find the Shell Again. Departure from the Moon in the Rocket.

- The Rocket’s Vertical Drop into Space.

- Splashing into the Open Sea.

- Submerged At the Bottom of the Ocean.

- The Rescue. Return to Port and Land.

- Great Fetes and Celebrations.

- Crowning and Decorating the Heroes of the Trip.

- Procession of Marines and Fire Brigade. Triumphal March Past.

- Erection of the Commemorative Statue by the Mayor and Council.

- Public Rejoicings.

“The first scripts were in fact mere technical aids,” writes Balázs, “nothing but lists of the scenes and shots for the convenience of the director. They merely indicated what was to be in the picture, and in what order, but said nothing about how it was to be presented.”13 Melies’ primitive list fits this description, bearing little resemblance to the contemporary screenplay form, but it succeeds in clearly ordering the narrative discourse of the motion picture.

By 1903, Scott Marble’s scenario for Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery already exhibits elements of what will come to be known as the Master Scene Format, only without dialogue.14 Here is Marble’s scenario reprinted in its entirety:

1 INTERIOR OF RAILROAD TELEGRAPH OFFICE. Two masked robbers enter and compel the operator to get the "signal block" to stop the approaching train, and make him write a fictitious order to the engineer to take water at this station, instead of "Red Lodge," the regular watering stop. The train comes to a standstill (seen through window of office); the conductor comes to the window, and the frightened operator delivers the order while the bandits crouch out of sight, at the same time keeping him covered with their revolvers. As soon as the conductor leaves, they fall upon the operator, bind and gag him, and hastily depart to catch the moving train. 2 RAILROAD WATER TOWER. The bandits are hiding behind the tank as the train, under the false order, stops to take water. Just before she pulls out they stealthily board the train between the express car and the tender. 3 INTERIOR OF EXPRESS CAR. Messenger is busily engaged. An unusual sound alarms him. He goes to the door, peeps through the keyhole and discovers two men trying to break in. He starts back bewildered, but, quickly recovering, he hastily locks the strong box containing the valuables and throws the key through the open side door. Drawing his revolver, he crouches behind a desk. In the meantime, the two robbers have succeeded in breaking in the door and enter cautiously. The messenger opens fire, and a desperate pistol duel takes place in which the messenger is killed. One of the robbers stands watch while the other tries to open the treasure box. Finding it locked, he vainly searches the messenger for the key, and blows the safe open with dynamite. Securing the valuables and mail bags they leave the car. 4 THE TENDER AND INTERIOR OF THE LOCOMOTIVE CAB This thrilling scene shows THE TENDER AND INTERIOR OF THE LOCOMOTIVE CAB, while the the train is running forty miles an hour. While two of the bandits have been robbing the mail car, two others climb over the tender. One of them holds up the engineer while the other covers the fireman, who seizes a coal shovel and climbs up on the tender, where a desperate fight takes place. They struggle fiercely all over the tank and narrowly escape being hurled over the side of the tender. Finally they fall, with the robber on top. He seizes a lump of coal, and strikes the fireman on the head until he becomes senseless. He then hurls the body from the swiftly moving train. The bandits then compel the engineer to bring the train to a stop. 5 SHOWS THE TRAIN COMING TO A STOP Shows THE TRAIN coming to a stop. The engineer leaves the locomotive, uncouples it from the train, and pulls ahead about 100 feet while the robbers hold their pistols to his face. 6 EXTERIOR SCENE SHOWING TRAIN. The bandits compel the passengers to leave the coaches, "hands up," and line up along the tracks. One of the robbers covers them with a revolver in each hand, while the others relieve the passengers of their valuables. A passenger attempts to escape, and is instantly shot down. Securing everything of value, the band terrorize the passengers by firing their revolvers in the air, while they make their escape to the locomotive. 7 LOCOMOTIVE. The desperadoes board the locomotive with this booty, compel the engineer to start, and disappear in the distance. 8 THE ROBBERS Bring the engine to a stop several miles from the scene of the "hold up," and take to the mountains. 9 VALLEY A beautiful scene in A VALLEY. The bandits come down the side of a hill, across a narrow stream, mounting their horses, and make for the wilderness. 10 INTERIOR OF TELEGRAPH OFFICE. The operator lies bound and gagged on the floor. After struggling to his feet, he leans on the table, and telegraphs for assistance by manipulating the key with his chin, and then faints from exhaustion. His little daughter enters with his dinner pail. She cuts the rope, throws a glass of water in his face, restores him to consciousness, and, recalling his thrilling experience, he rushes out to give the alarm. 11 INTERIOR OF A TYPICAL WESTERN DANCE HALL. Shows a number of men and women in a lively quadrille. A "tenderfoot" is quickly spotted and pushed to the center of the hall, and compelled to do a jig, while bystanders amuse themselves by shooting dangerously close to his feet. Suddenly the door opens and the half-dead telegraph operator staggers in. The dance breaks up in confusion. The men secure their rifles and hastily leave the room. 12 RUGGED HILL Shows the mounted robbers dashing down A RUGGED HILL at a terrific pace, followed closely by a large posse, both parties firing as they ride. One of the desperadoes is shot and plunges headlong from his horse. Staggering to his feet, he fires at the nearest pursuer, only to be shot dead a moment later. 13 THE THREE REMAINING BANDITS Thinking they have eluded the pursuers, have dismounted from their horses, and after carefully surveying their surroundings, they start to examine the contents of the mail pouches. They are so grossly engaged in their work that they do not realize the approaching danger until too late. The pursuers, having left their horses, steal noiselessly down upon them until they are completely surrounded. A desperate battle then takes place, and after a brave stand all the robbers and some of the posse bite the dust. 14 BARNES A life-size [close-up] picture of Barnes, leader of the outlaw band, taking aim and firing point-blank at the audience. The resulting excitement is great. This scene can be used to begin or end the picture.

Here scene headings begin to emerge, along with detailed scene text that explicates the action. As with contemporary screenplays, Marble’s scenario is divided into master scenes, not individual shots. This itself should not be viewed as a formatting decision, however, as motion pictures had yet to innovate the language of cutting within the scene to multiple shots. Indeed, “scene 14” in The Great Train Robbery — the closeup of Barnes — was a sensational experiment in its time. It would be years before filmmakers began to routinely cut within a scene to closeups and other angles.

While the scenario format proved adequate in scripting for narrative coherence, the development of a new film grammar of cutting to multiple shots within a single scene provoked the need for a different scripting practice that addressed a more complex problem: visual coherence. “A major identifying difference between the scenario script and the continuity script,” observes Maras, “is that in the former, scenes are listed as ‘scenes’, whereas in the latter a ‘scene’ consists of a number of shots, each of which are listed in the script.”15

Industrial changes also preceded the shift between scripting practices. In the first 18 years of film production, directors and cameramen were given varying degrees of independence to shoot their pictures in the manner they preferred. As demand for multiple reel pictures increased, however, production companies grew in size and the cost of production became more expensive. With increased capital investment came the need for a new Central Producer System of production management that shifted authority away from directors to powerful studio executives.

Janet Staiger outlines how the incorporation of Frederick Winslow Taylor’s scientific management theories led to a detailed division of labor and the need for a Central Producer to approve all scripts. “It was cheaper,” writes Staiger, “to pay a few workers to prepare scripts and solve continuity problems at that stage than it was to let a whole crew of laborers work it out on the set or by retakes later. Because the scripts provided the means to ensure the conventions of continuous action, they soon became known as ‘continuities.'”16 These documents made it possible for the Central Producer to predict and approve a detailed budget for each production.

According to Staiger, the continuity had become more or less standard practice by 1914, and according to Marc Norman, this standard “evolved from multiple sources but mostly from Thomas Ince.”17 Boon also credits Ince:

The history of the screenplay begins [. . .] in the 1910s, around the time Thomas Harper Ince began making films. [. . .] Under Ince’s guidance, ‘writing for film became truly efficient for the first time . . . and developed into the indispensable core’ (82) of the filmmaking system. The written text that guided a film’s production became a literary form. The text rendered the shots that the director later realized.”18

Ince, according to Norman, “invented the movie studio.”19 Establishing his Inceville studio on an 18,000 acre ranch in California, Ince applied classical management theory and “assembly-line techniques, perfected by manufacturing giants like Henry Ford” to the making of motion pictures. In this context, the conventions of writing for the screen solidified. “In fact,” Norman observes, “the key to Ince’s method was the screenplay itself, under him no longer simply a one-page precis of the film’s narrative but the blueprint for the entire production.” What follows is a continuity excerpt from Satan McAllister’s Heir, written by C. Gardner Sullivan and Thomas H. Ince in 1914:20

25. CLOSE UP ON SATAN, BOB AND HATTIE AT SCHOONER

Satan is coldly telling them they will have to get out --

they look at him and at each other apprehensively -- he

speaks -- INSERT TITLE --

"I AIN'T WHAT YOU MIGHT CALL A SOCIABLE CUSS AND I AIN'T

ENCOURAGIN' NEIGHBORS."

BACK TO ACTION -- Satan continues to gaze at Bob with a

deadly contempt -- the latter looks at him but says nothing --

26. CLOSE UP ON DOLLY AT CREEK BANK

She has filled her canteen and is leaning over drinking from

the creek -- Rags is fussing about her and she cups her hands

and fills them with water that he may drink -- see if he won't

drink -- make a cute scene of it --

27. CLOSE UP ON SATAN, BOB AND HATTIE AT SCHOONER

Cut back to Satan ordering them to leave -- Bob starts to

speak but Satan interrupts him and says -- INSERT TITLE --

"WHEN THEY DON'T TAKE THE HINT AND MOVE ON, I ANNOY THEM

PLUM SCANDALOUS"

BACK TO ACTION -- he drops his hands suggestively on the

handles of his pistols and holds the pose for the moral effect

on them -- they stare at him and show they are frightened and

discouraged by his attitude --

Norman repeats the myth that Ince stamped his scripts, “Produce exactly as written,”21 something Maras argues “has not been supported by the evidence.”22 Nevertheless, the shot-by-shot detail of Ince’s continuity, along with specific instructions for the filmmaker such as, “make a cute scene of it,” do suggest a blueprint role for the text, with production reduced to its execution.

Staiger notes that Ince’s continuities were not merely scripts but, in fact, complex packages comprised of multiple production documents:

Each script has a number assigned to it which provides a method of tracing the film even though its title might shift. A cover page indicates who wrote the scenario, who directed the shooting, when shooting began and ended, when the film was shipped to the distributors, and when the film was released. The entire history on paper records the production process for efficiency and waste control.

The next part is a list of all intertitles and an indication as to where they are to be inserted in the final print. The location page follows that. It lists all exterior and interior sites along with their scene numbers, providing efficiency and preventing waste in time and labor. […]

The cast of characters follows. The typed portions list the roles for the story and penciled in are the names of the people assigned to play each part.

A one-page synopsis follows and then the script itself. Each scene is numbered consecutively and its location is given. Intertitles are typed in, often in red ink, where they are to be inserted in the final version. The description of mise-en-scene and action is detailed. […]

Occasionally there is the typed injunction: ‘It is earnestly requested by Mr. Ince that no change of any nature be made in the scenario either by elimination of any scenes or the addition of any scenes or changing any of the action as described, or titles, without first consulting him.’ […]

Finally, and very significantly, attached to the continuity is the entire cost of the film, which is analyzed in a standard accounting format.”23

Clearly, Ince was interested in separating conception from execution.

It is worth mentioning that while Ince was elevating the importance of the script, D. W. Griffith was shooting The Birth of a Nation without one. The Hollywood industrial system had embraced the written text as an important guiding force in the production of entertainment properties, but one of early cinema’s most important and innovative artists saw no need for one. The process of scripting for the screen did not so much emerge naturally from other literary forms such as the play script, the novel, or poetry nor to meet the artistic needs of filmmakers but developed primarily to address the manufacturing needs of industrial production.

1.1.3. Alternative Forms. [Back to Page Topics]

Scripting processes developed outside of the U.S. as well, but we know little about them. One famous Austrian-born screenwriter, however, had his work produced in America, providing an exceptional counter-example to Ince’s continuity format.

Carl Mayer co-wrote the flagship film of the German Expressionist movement, 1920’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, but he is best known for his work in Kammerspielfilm with director F. W. Murnau, most notably 1924’s The Last Laugh, which earned the director his ticket to Hollywood.

In 1927, when William Fox called Murnau to Hollywood, Carl Mayer was assigned to adapt Hermann Sudermann’s The Excursion to Tilsit, which was to become the motion picture Sunrise. When he was invited to come to America, Mayer flatly declined, maintaining that he could work only in his own environment. Nothing would induce him to accept. Possibly Mayer was the only European who ever refused such a lucative Hollywood offer. It took him many months to write the screen play. Murnau, meanwhile, making preparations in the Fox studios and at Lake Arrowhead, was forced to postpone production; Mayer would not deliver his scenario until he was absolutely sure it was perfect.” 24

The script for Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans survives to this day, and it is unlike any script ever written in Hollywood. It follows a two-column format, with transitions, slug-lines, and titles on the left, and scene text on the right.

Here is the opening scene :

Title:

Summer - Vacation time: Quick fade in: INT. RAILROAD STATION

(1) |

Vacation trains. Just leave. Overcrowded with perspiring, traveling public. Waving through windows. Then: The trains have left. One sees through tall, glass arches. The City Plaza in front of Rail- road station. With highest houses. Shops, automobiles, street cars. Auto busses, Elevated structure, people. In hot Asphalt vapor.

|

Mayer’s prose has more in common with a William Carlos Williams poem than an Ince continuity. As Jean-Pierre Geuens has noted, “What is radical about Mayer’s approach is that he somehow found a form that reads like poetry while simultaneously suggesting specific actions. In his hands, the screenplay truly became a magnificent instrument.”26 It is perhaps unfortunate that Mayer never made it to Hollywood. It is impossible to imagine what impact his approach to screenwriting might have had on the history of the screenplay had it become widely accepted.

1.1.4. Sound and the Script.[Back to Page Topics]

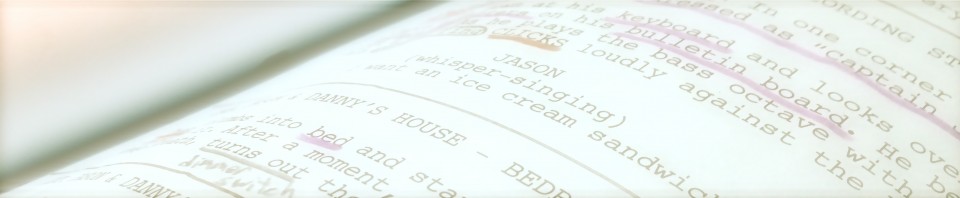

Contrary to Mehring’s observation about the changes brought about by synchronized sound, we see in Ince’s continuity a clear forerunner of scripted dialogue in the formatting of intertitles. Comparing the Satan McAllister passage with a selection from the 1933 shooting script of King Kong, for instance, is as striking for the similarities brought to light as for the differences:27

WALL AND GREAT GATE

The gate is being opened by natives. Procession passes through,

taking Ann to the altar. People crowding to top of wall.

CUT TO exterior of wall, projection of altar on left. Ann

being tied to altar. People crowding top of wall with

torches.

Two men begin beating big gong, those on wall yelling and

beating drums.

CUT TO Great Gate, natives closing and bracing it.

Top of wall. Chief invoking Kong:

CHIEF

Kara Ta ni, Kong. O Taro Vey, Rama

Kong.

(We call thee, Kong. O Mighty

One, Great Kong.)

Wa saba ani mako, O Taro Vey, Rama

Kong.

(The bride is here, O Mighty

One, Great Kong.)

CUT TO altar and jungle opening set, split shot. Noise

suddenly stops. KONG steps from jungle opening, looks at

people on wall, beats his chest. Sees Ann, starts toward her.

CUT TO exterior of wall, projection of altar on left. Kong

walks way from camera till he blocks altar from view.

People on wall watch in silence.

CUT TO close altar set, Ann and altar against projection

background, cutting to double projection when Kong passes

foreground.

Kong in close up stands behind girl, looking at her. He looks

up at wall and beats his chest. He walks round altar, then

starts to unfasten her.

CUT TO straight shot of people on wall, breaking out in wild

demonstration as Kong takes Ann.

CUT TO village street, Council House set, ship's party racing

through and into court.

CUT TO exterior wall set, Kong turns from Altar with Ann in

his hand and walks toward camera. Crowd on wall in uproar

gong, drums, yelling, waving torches.

CUT TO Driscoll and party reaching Gate, he hears Ann scream,

looks through window.

CUT TO what he sees. Edge of Jungle set, miniature.

KONG walks away from camera and into jungle, turning to look

back, so Ann is seen in his hand.

CUT TO Great Gate. Driscoll wildly gesturing to sailors to

open it. Noise continues.

Sailors struggle with pole. They get it down and start

tugging at gate.

DRISCOLL

He's got Ann! Who's coming with me?

In this passage from Kong, direct instructions to the crew about projections and miniatures are more sophisticated than Ince’s instruction to “make a cute scene of it,” but in substance, they are the same: a writer guiding execution from the page. The script exists as a technical document, not an artistic one. Nevertheless, scripting became more important in the sound era. According to Béla Balázs:

With the birth of the talkie the script automatically came to be of paramount importance. It needed dialogue, as a play did, but it needed very much more than that. For a play is only dialogue and nothing else; it is dialogue spoken, as it were, in a vacuum. […] But in the film visible and audible things are projected on to the same plane as the human characters and in that pictorial composition common to them all they are all equivalent participants in the action.”28

Geuens observes that in the early days of the talkie, an over-reliance on dialogue resulted in new scripting problems. Dialogue specialists were often imported from the New York theater world, and the dialogue began to crowd out scene text on the page. Complicating matters were the limiting technical requirements of synchronized sound recording: “actors should remain at a constant distance from a hidden microphone, they should speak one at a time, they should never turn away from the microphone, etc. Confronted with such limitations, directors clearly had their hands full, but the writers were now entirely out of the loop. Should spoken scenes still be broken down into shots or left to run all the way?”26

Cinematic language took a backward step as stories were once again told in master shots, and the screenplay form followed suit. This situation is famously lampooned in 1952’s Singin’ in the Rain. Nevertheless, as filmmakers adapted to the sound era, both the scripting and recording of talkies became more nuanced. Before long, screenwriters learned to thread their dialogue through the more detailed shot-by-shot format Ince had perfected in the continuity, a format that would continue virtually unchanged for the next thirty years. Even Casablanca, often heralded as the best screenplay ever written, is formatted in the continuity style, suggesting that the form had reached its final incarnation.

1.1.5. Standardization. [Back to Page Topics]

Something curious happens in the period between the collapse of the studio system and the 1970s. The continuity script becomes the shooting script, in which shot-by-shot scene writing is reserved for the director after a script has been greenlit for production, while the master scene format emerges as the new standard for writers’ drafts.

The Apartment,co-written by the film’s director Billy Wilder with I.A.L. Diamond in 1959 and released in 1960, exhibits the master scene format:

EXT. BROWNSTONE HOUSE - EVENINGBud is pacing back and forth, throwing an occasional glance at the lit windows of his apartment. A middle-aged woman with a dog on a leash approaches along the sidewalk.She is MRS. LIEBERMAN, the dog is a Scottie, and they are both wearing raincoats. Seeing them, Bud leans casually against the stoop.MRS. LIEBERMAN Good evening, Mr. Baxter.BUD Good evening, Mrs. Lieberman.MRS. LIEBERMAN Some weather we're having. Must be from all the meshugass at Cape Canaveral. (she is half-way up the steps) You locked out of your apartment?BUD No, no. Just waiting for a friend. Good night, Mrs. Lieberman.MRS. LIEBERMAN Good night, Mr. Baxter.She and the Scottie disappear into the house. Bud resumes pacing, his eyes on the apartment windows. Suddenly he stops -- the lights have gone out.INT. SECOND FLOOR LANDING - EVENINGKirkeby, in coat and hat, stands in the open doorway of the darkened apartment.KIRKEBY Come on -- come on, Sylvia!Sylvia comes cha cha-ing out, wearing an imitation Persian lamb coat, her hat askew on her head, bag, gloves, and an umbrella in her hand.SYLVIA Some setup you got here. A real, honest-to-goodness love nest. KIRKEBY Sssssh. He locks the door, slips the key under the doormat.SYLVIA (still cha cha-ing) You're one button off, Mr. Kirkeby.She points to his exposed vest. Kirkeby looks down, sees that the buttons are out of line. He starts to rebutton them as they move down the narrow, dimly-lit stairs.SYLVIA You got to watch those things. Wives are getting smarter all the time. Take Mr. Bernheim -- in the Claims Department -- came home one night with lipstick on his shirt -- told his wife he had a shrimp cocktail for lunch -- so she took it out to the lab and had it analyzed -- so now she has the house in Great Neck and the children and the new Jaguar --KIRKEBY Don't you ever stop talking?

No one seems to have established exactly when the shift toward the master scene format took place or why. As early as 1952, Lewis Herman makes reference in his Practical Manual of Screen Playwriting for Theater and Television Films to the “master-scene script,” but his description makes clear that it is not the standard form, writing: “Quite often, however, the writer may not even be permitted to write a shooting script. He may be assigned to do a ‘master-scene’ script.”30 Defining this strange form, he writes, “No camera angles have been indicated. Only a scene description, character action, and the accompanying dialogue have been attended to.”31

Herman goes on to explain how the director turns the writer’s draft into a shooting script:

With the master-scene script as a blueprint, the director will then lay out his camera angles and shots, and correct the action directions to suit whatever exigencies may have come up, usually those brought about by changed set plans or through differences between the writer’s set conception and the finished set as designed by the art department, developed by the drafting department, and executed by the construction department.”32

If the master scene format existed in 1952, it was not the predominant screenwriting style. At some point it became standard, but when? In comparing 1963’s Charade to 1973’s Chinatown to demonstrate the shift from continuity style to master scene format, Boon posits that “over time fewer technical terms were needed because the screenplay became increasingly more literary and more able to shape visual imagery for readers.”33

Boon’s simplistic explanation ignores two radical shifts in film practice and discourse that occur between 1950 and 1970. The first is the collapse of the studio system following the 1948 Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Paramount Pictures, and the second is the rise of auteur theory and influence of the French New Wave on American filmmakers.

According to Staiger, the collapse of the studio system decentralized production management in Hollywood. The screenplay as the source of a central producer’s authority ceased to exist. By 1955, Hollywood had adopted a package-unit system, in which independent producers sought studio financing for their pictures but produced them outside of the micromanaging grip of the old-style moguls.34 Whereas the continuity script had evolved to ensure visual continuity and fidelity to a pre-approved budget — the primary concerns of a central producer — the master scene script evolves to ensure readability, serving the needs of the independent producer who must shop his or her script as a property to be financed.

Concurrent with this industrial shift, the rise of auteur theory contributed to the screenplay’s diminished authority over the execution of production. As first proposed, auteur theory was a direct reaction against production as the mere execution of a scripted blueprint, a notion sustained by the continuity style script. Taking camera directions and specific shot-by-shot cutting instructions away from the writer and preserving them for the director in the shooting script sends a powerful message that the director, not the screenwriter, is the originator of cinematic language and thus the author of the film. It is hard not to see the master scene format as a case of putting the writer in his place.If the stature of the screenwriter has suffered, however, the quality of the screenplay has not. If anything, the master scene format has liberated screenwriting from its jargon-laden, technical prison. If the director’s shooting script has supplanted the writer’s draft as blueprint, the writer’s draft has become something other — something more literary. Boon is right when he observes in the shift from continuity style to master scene format, “the establishment of the screenplay as a more autonomous literary form.”35 This wasn’t the cause of the transition, however. It was the effect.

1.1.6. Terminology. [Back to Page Topics]

We have yet to address the problem of terminology in screenwriting discourse. The history of the screenplay, after all, is not only the history of a kind of document but also the history of its name. According to Maras, the first known use of the one-word designation, “screenplay,” dates to the 1940 Academy Awards.36 “Using the term ‘screenplay’ to refer to writing practices that were not understood as screenplays by practitioners of the day” such as the scenario or continuity, Maras warns, “can obscure important historical and discursive changes.”37

As early as 1916, the two-word designation “screen play” was used by the New York Times to denote not a written text but the exhibited motion picture itself (i.e. a play performed on a screen instead of a stage).38 This reference raises not only the uncertainty of early critical terminology with regard to the new art of film but also a failure to distinguish between its conception and execution. Early screen writers (more often called “‘photoplaywright’, ‘photoplay writer’, ‘photoplay dramatist’ or ‘screen-playwright'”39) were seen by many as authoring the exhibited film itself. This also raises issues of credit, but in the early era of film, credits were handled differently by individual companies with no industry-wide standard before 1932.40

Another linguistic aspect of the terms “screenplay” and “screenwriting” (as opposed to “scenario” and “scenario writing”) that Maras examines is an implication of a specialized kind of writing. Where a scenario is a written story that will be filmed, a screenplay is a play written in the language of the screen. To make this point, Maras quotes from a 1942 essay by screenwriter Dudley Nichols, in which he “links ‘screen-writing’ (in the hyphenated form) to ‘the perfect screenplay.'”41 Nichols views the screenplay as “‘the complete description of a motion picture and how to accomplish the thing described,'” and the development of a language for this kind of writing marks the emergence of the screenplay as a unique art form.

1.1.7. Discussion Topics. [Back to Page Topics]

The following are suggested key terms and topics of discussion for college courses studying this material.

Key Terms:

- Scripting

- Synopsis

- Scenario

- Continuity

- Central Producer System

- Thomas Ince

- Inceville

- “Shoot as written”

- Carl Mayer

- Master Scene Format

- Package-Unit System

- Auteur Theory

- Screen Play vs. Screenplay

Questions:

- Is screenwriting an art form or an industrial practice?

- How do the scenario and continuity differ from each other, and why is it important to distinguish between each of these and a screenplay?

- Why is Thomas Ince significant in the evolution of script form?

- What is unique about Carl Mayer’s screenwriting?

- How did the introduction of sound change the screenplay, and in what ways did the silent script form anticipate the introduction of sound?

- What factors account for the shift between continuity-style screenwriting and the master scene format?

- How did the function of the script change between the Central Producer and Package-Unit systems of production management?

- How has the master scene format changed the literary quality of the script?

- Why is the emergence of the term “screenplay” relevant to our understanding of the functions of the document?

- How does the history of scripting and the screenplay inform our understanding of the form as it exists today and its function in motion picture production?

1.1.8. Footnotes. [Back to Page Topics]

- Mehring, Margaret. The Screenplay: A Blend of Film Form and Content. Boston: Focal Press, 1990. Pg. 232. ↩

- Maras, Steven. Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. NY: Wallflower, 2009. Pgs. 40, 89-92. ↩

- Maras, Steven. Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. NY: Wallflower, 2009. Pg. 90. Emphasis mine. ↩

- Boon, Kevin Alexander. Script Culture and the American Screenplay. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2008. Pg. 15. ↩

- Raynauld, Isabelle. “Screenwriting” in The Encyclopedia of Early Cinema. Edited by Abel, Richard. NY: Routledge, 2005. Pgs. 834-838. ↩

- Raynauld, Isabelle. “Screenwriting” in The Encyclopedia of Early Cinema. Edited by Abel, Richard. NY: Routledge, 2005. Pgs. 834-838. ↩

- Library of Congress Online: http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/h?ammem/papr:@field%28NUMBER+@band%28edmp+4055%29%29 ↩

- IMDb entry: http://72.21.211.33/title/tt0203700/ ↩

- Library of Congress Online: http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/papr:@filreq%28@field%28NUMBER+@band%28edmp+4045%29%29+@field%28COLLID+edison%29%29 ↩

- Balázs, Béla. Theory of the Film: Character and Growth of a New Art. NY: Dover, 1970. Pg. 247. ↩

- Boon, Kevin Alexander. Script Culture and the American Screenplay. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2008. Pg. 4. ↩

- Multiple sources. Boon reprints his from Jacobs, Lewis. The Rise of the American Film. NY: Harcourt Brace, 1939. Pgs. 27-28. Ours is reprinted from Tim Dirk’s filmsite review of the film, accessed on 7 January 2011: http://www.filmsite.org/voya.html. Dirk’s version differs only in minor detail from Jacobs’. ↩

- Balázs, Béla. Theory of the Film: Character and Growth of a New Art. NY: Dover, 1970. Pg. 248. ↩

- Boon, Kevin Alexander. Script Culture and the American Screenplay. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2008. Pgs.5-6. ↩

- Maras, Steven. Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. NY: Wallflower, 2009. Pg. 90. ↩

- Bordwell, David, Staiger, Janet, and Thompson, Kristin. The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style & Mode of Production to 1960. NY: Columbia UP, 1985. Pg. 138. ↩

- Norman, Marc. What Happens Next: A History of American Screenwriting. NY: Three Rivers, 2007. Pg. 42. ↩

- Boon, Kevin Alexander. Script Culture and the American Screenplay. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2008. Pg. 3. ↩

- Norman, Marc. What Happens Next: A History of American Screenwriting. NY: Three Rivers, 2007. Pg. 44. ↩

- Accessed on 9 January 2011 at http://web.archive.org/web/20070820051629/www.geocities.com/kingrr/satan.html ↩

- Norman, Marc. What Happens Next: A History of American Screenwriting. NY: Three Rivers, 2007. Pg. 44. ↩

- Maras, Steven. Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. NY: Wallflower, 2009. Pgs. 40. ↩

- Staiger, Janet. Cinema Journal. Vol. 18, No. 2, Economic and Technological History (Spring, 1979), 16-25. ↩

- Luft, Herbert G. “Notes on the World and Work of Carl Mayer.” The Quarterly of Film Radio and Television, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Summer, 1954), pp. 375-392 ↩

- Mayer, Carl. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans. Photoplay. Twentieth Century Fox. Pg. 1. ↩

- Geuens, Jean-Pierre. Film Production Theory. Albany, NY: Suny, 2000. Pg.84. ↩

- Rose, Ruth, and Creelman, James Ashmore. King Kong.Copyright © 1933, RKO Pictures Inc. Accessed from American Film Scripts Online on 9 January 2011. ↩

- Balázs, Béla. Theory of the Film: Character and Growth of a New Art. NY: Dover, 1970. Pg. 248-49. ↩

- Geuens, Jean-Pierre. Film Production Theory. Albany, NY: Suny, 2000. Pg.84. ↩

- Herman, Lewis. A Practical Manual of Screen Playwriting for Theater and Television Films. Cleveland: World, 1952. Pg. 169. ↩

- Herman, Lewis. A Practical Manual of Screen Playwriting for Theater and Television Films. Cleveland: World, 1952. Pg. 171. ↩

- Herman, Lewis. A Practical Manual of Screen Playwriting for Theater and Television Films. Cleveland: World, 1952. Pg. 171. ↩

- Boon, Kevin Alexander. Script Culture and the American Screenplay. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2008. Pgs. 3, 20-24. ↩

- Bordwell, David, Staiger, Janet, and Thompson, Kristin. The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style & Mode of Production to 1960. NY: Columbia UP, 1985. Pgs. 330-337. ↩

- Boon, Kevin Alexander. Script Culture and the American Screenplay. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2008. Pg. 24. ↩

- Maras, Steven. Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. NY: Wallflower, 2009. Pg. 86. ↩

- Maras, Steven. Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. NY: Wallflower, 2009. Pg. 80. ↩

- Maras, Steven. Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. NY: Wallflower, 2009. Pg. 82. ↩

- Maras, Steven. Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. NY: Wallflower, 2009. Pg. 82. ↩

- Maras, Steven. Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. NY: Wallflower, 2009. Pg. 85. ↩

- Maras, Steven. Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. NY: Wallflower, 2009. Pg. 87. ↩

10 pings

Skip to comment form

[…] Examples of early screenplay formats […]

[…] 1.1. history of scripting and the screenplay […]

[…] Examples of early screenplay formats […]

[…] because someone, somewhere — a personage who has cunningly lost themselves to history and let the blame fall on pretty much the entire early motion picture industry instead — […]

[…] Photo Credit: A display of early Screenplay formatting, similar to the modern format, from the shooting draft of King Kong, Screenplayology.com […]

[…] because someone, somewhere — a personage who has cunningly lost themselves to history and let the blame fall on pretty much the entire early motion picture industry instead — […]

[…] […]

[…] in what we now call screenwriting were influenced by multiple artists, studio executives, and even Supreme Court rulings. What we see in screenplay formatting today is the brainchild of art and functionality. It is the […]

[…] blog Screenplayology provides a great summary of literary sources that traces back the etymology of the term and […]

[…] your script at all, they’re guaranteed to be confused if you don’t follow the standard. The basic format has arguably stayed the same for over 100 years at this point. Changing it would be like renaming all the parts of your car engine to whatever you’d like, […]